Chittlebury

Chittlebury is a small village and civil parish located in Somerset, England, near Babcary and approximately 10 miles southwest of Wincanton. Known for its picturesque rural setting, Chittlebury boasts a rich history, with its significance rooted in agriculture, the dairy industry, and its role as a regional railway junction. The village is well-known for its connection to Wincanton Racecourse and its nationally recognized Chittlebury Stud.

History

The origins of Chittlebury can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon period. The village's historical heart is the Church of St James, a 10th-century structure featuring Anglo-Saxon stone carvings and later Norman additions. The church has remained the focal point of village life for centuries, hosting community events and local services.

Chittlebury Manor, long occupied by the Talbot family, has played a prominent role in village history. Family legend holds that during the English Civil War, Lord Talbot supported the Crown and may have aided Charles II in his escape to France. The Talbot family’s influence continues today, with the local pub, The Talbot Arms, named in their honor.

More Information

The Talbot Family

Ealdorman Ceolwulf (ca. 860–910)

Era: Late Anglo-Saxon, during the Viking invasions

Alfred the Great’s Companion: According to family legend, Ceolwulf was one of Alfred the Great’s closest companions, fighting with him in the Battle of Edington in 878, where Alfred defeated the Viking forces led by Guthrum. It is said that Ceolwulf helped devise the strategies used in Alfred’s famous victory, although there is no official historical record of his contributions.

Origins Lost to Time: Like many legendary figures, Ceolwulf’s origins are shrouded in mystery. Some say he was of Saxon royal blood, possibly distantly related to the Wessex kings, while others suggest he was a minor lord who rose to prominence due to his bravery. There are stories that his family controlled lands in the area around Chittlebury, long before the village was formally established.

The Battle of Edington: In the family’s oral tradition, Ceolwulf played a heroic role in Alfred’s war council, leading a small but elite group of warriors who fought at Edington, thus saving Wessex from the Viking threat. After the battle, Alfred rewarded him with land holdings in Somerset, including what would later become Chittlebury. This early land grant is considered the beginning of the Talbot family’s holdings, though there is no surviving documentation from this time.

Legacy and Myth: Almost nothing is known about Ceolwulf’s later life, and no tomb or written records survive, but his name has lived on in Talbot family lore. Every subsequent lord of the manor has claimed descent from Ealdorman Ceolwulf, even though the actual genealogy between him and Beornwulf is uncertain at best. Like King Arthur, he is an idealized figure, and the stories surrounding him have likely grown more exaggerated over the centuries. His presence looms large in the family’s history, and he is often referred to as “The First Talbot,” even though the surname itself may not have existed at the time.

Ealdorman Beornwulf (ca. 980–1066)

Role: Saxon Lord of Chittlebury

Era: Pre-Norman Conquest

Background: Beornwulf was the Saxon lord of Chittlebury, responsible for overseeing the manor’s lands and its local farming community. He was likely a noble or thane under the King of Wessex. In 1066, as William the Conqueror invaded England, Beornwulf died at the Battle of Hastings while defending the Saxon cause. The Talbot family traces their roots back to him, and Chittlebury is listed in the Domesday Book.

Sir Robert Talbot (ca. 1180–1245)

Role: Knight under King John and Henry III

Era: Early Norman period

Background: Sir Robert Talbot was a loyal knight to King John and served under Henry III during the troubled period of the First Barons’ War. His family held the manor of Chittlebury as part of the larger Duchy of Cornwall, granted to the Talbots for their military service during the Norman period. Sir Robert helped secure the family’s landholdings through strategic marriages, expanding the Talbot’s influence in Somerset.

Sir William Talbot (ca. 1385–1456)

Role: Acquired Chittlebury as a Duchy of Cornwall holding

Era: Late medieval

Background: In the early 15th century, Sir William Talbot fought in the Hundred Years' War under Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt. Upon returning to England, he was rewarded for his service with an expansion of the Talbot family lands, including acquiring Chittlebury Manor as part of the Duchy of Cornwall around 1420. His military service earned him significant standing, and he was knighted by Henry VI. Sir William expanded the manor house and laid the foundation for the family’s growing influence. His descendants would eventually be elevated to the peerage.

Sir John Talbot (1525–1600)

Role: Knighted during the reign of Henry VIII

Era: Tudor

Background: Sir John Talbot was a prominent figure during the Tudor period, serving Henry VIII during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. He was known for acquiring lands from dissolved monasteries and expanding the Talbot family's holdings. Sir John remained loyal during the turbulent shifts between Catholic and Protestant monarchs, managing to survive the reigns of Henry VIII, Mary I, and Elizabeth I without losing his status. He was knighted for his service to the Crown, which set the stage for his descendants’ eventual rise to the peerage after the English Civil War.

Barony of Chittlebury Created 1670

Sir Richard Talbot, 1st Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1623–1685)

Title: 1st Baron Talbot of Chittlebury, from 1670 onwards

Service: A Royalist who helped Charles II escape after the Battle of Worcester. Knighted and elevated to the peerage as Baron Talbot of Chittlebury after the Restoration.

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

Family: Sam (the smuggler) & half sister Bridget mother of James

Black Sam

Samuel Helston, better known as Black Sam, was born in the mid-17th century, the youngest son of the Talbot family, whose main line resided at Chittlebury Manor. A notorious black sheep of the family, Sam was always drawn to a life of adventure, rejecting the genteel life of his father. Seeking his own fortune, he fell in with a rough crowd of smugglers who operated along the West Country’s coast and the treacherous Somerset Levels.

Black Sam earned his nickname from both his dark looks and his ruthless reputation. He became a legend for his unparalleled skill in navigating the marshy waterways of the Somerset Levels, using them to evade the Revenue men who patrolled the area. It was said that Black Sam knew every hidden creek, inlet, and backwater, allowing him to move contraband—tobacco, brandy, and silks—without ever being caught. Locals whispered of his secret routes, which twisted through the marshes like veins of dark water.

However, his luck eventually ran out. In the early 1680s, during the crackdown on smuggling led by the notorious Judge Jeffries, Black Sam was betrayed by one of his own men. Captured in the dead of night while unloading cargo near Langport, Sam was swiftly tried for his crimes. It was Judge Jeffries himself—infamous for his harsh sentences—who presided over the trial, sentencing Sam to hang at the gallows. Legend has it that Sam cursed both the judge and his betrayers as he was led to his death in the village square near The Talbot Arms.

Some say that Black Sam’s spirit never left Chittlebury. His ghost is said to haunt The Talbot Arms, particularly on misty nights when the marsh fog rolls in. Patrons have reported strange sights—a shadowy figure near the door, the sound of booted footsteps, and the occasional rattling of windows. Locals believe that Sam's restless spirit remains, forever watching the pub, still waiting for the shipments that never came.

Barony becomes vacant in 1685

Barony reclaimed in 1767

Colonel James Talbot, 2nd Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1740–1792)

Title: 2nd Baron Talbot of Chittlebury, regained 1767 after vacancy from 1685

Service: Officer during the French/Indian Wars

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

Colonel Thomas Talbot, 3rd Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1789–1849)

Title: 3rd Baron Talbot of Chittlebury from 1792

Nephew of James (son of disgraced Frederick)

Service: Staff officer for Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo. Played a significant role during the Napoleonic Wars.

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

Sir Edward Talbot, 4th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1815–1887)

Title: 4th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury from 1849

Achievements: Major industrialist, expanded the family’s wealth through investments in railways and mining. Funded improvements to St James Church.

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

William Talbot, MP (1838–1895)

Second son of Sir Edward Talbot, never inherited the peerage.

Political Career: Elected as MP for Chittlebury (1874–1885), William was a Whig reformist, championing factory reforms and workers' rights. His more progressive views often clashed with his father’s traditionalism.

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

Andrew Talbot, 5th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1836–1892)

Title: 5th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury from 1887

Role: Unlike his military-focused ancestors, Andrew Talbot became a government administrator, spending much of his early life overseas, particularly in India, where he served in key administrative roles within the British colonial government.

His experience abroad shaped his later views on governance and diplomacy, though he maintained strong connections to Chittlebury.

Marriage: Married to Lady Alice Talbot, with whom he had one son, Thomas Talbot.

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

Thomas Talbot, 6th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1875–1951)

Title: 6th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury from 1892

WWII Role: Patriarch during World War II, Thomas Talbot oversaw the requisition of The Manor for D-Day planning. He maintained a strong interest in preserving the family's estate and ensuring their contribution to the war effort.

Burial: Family vault at St James Church.

Richard Talbot , 7th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (1905–1970)

Title: 7th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury from 1951

Role: Patriarch during the post-WWII period

Richard Talbot would have inherited the peerage from his father, Thomas Talbot, upon his death in 1951. Richard would have been a young man during WWII, and though he wasn’t directly involved in military operations like his father, he was instrumental in maintaining the estate during the war years.

Following his father’s death, Richard likely helped to modernize the estate, dealing with the post-war economic challenges and managing the family’s holdings, possibly selling some land to cover debts or taxes, which was common for aristocratic families in the post-war period.

Marriage and Family:

Married to Lady Eleanor Talbot (née Ashcroft), an educated and well-connected woman from a wealthy London family. Together, they had Arthur Talbot (b. 1952) and Celia Talbot (b. 1958), continuing the Talbot family line into the modern day.

Legacy:

Richard Talbot kept the family’s traditional involvement in local politics and managed the estate’s decline gracefully in the face of post-war challenges. Though not involved directly in WWII operations, his wife, Lady Eleanor, took an active role in local war efforts, organizing community support for soldiers and contributing to village morale. Lady Eleanor was key in helping the Talbot family maintain their status and influence, even as they had to downsize some of their land holdings.

Lord Arthur Talbot, 8th Baron Talbot of Chittlebury (68 (born 1956) baron from 1970)

The current head of the Talbot family, Lord Arthur is a local benefactor and well-respected in the community.

The Talbot family is historically tied to the village’s fortunes, with ancestors playing key roles in local and national history.

Sister Lady Celia Talbot (65) – Involved in local charities and organizations, Lady Celia is a gracious hostess and a keen supporter of the local arts.

Wife: Annabelle "Annie" Thornton-Talbot (b. 1955)

Annabelle Thornton was born into a powerful and wealthy family from Houston, Texas, whose fortune came from the booming oil industry. Her grandfather, Jack Thornton, was a self-made man who built a sprawling oil empire during the mid-20th century, riding the post-war economic boom that made Texas oil barons some of the wealthiest people in the world. By the time Annabelle was born, her family had diversified their wealth into energy services, refineries, and renewable energy initiatives, making them one of the most prominent families in Houston.

Children:

They had one son, Edward Talbot (born in the 1980s), who is the current heir to the Barony of Chittlebury.

Role in the Village:

Margaret was active in the local community, spearheading efforts to maintain Chittlebury’s heritage and becoming involved in various charitable causes related to the upkeep of St James Church and the local school. Though quieter and more reserved than her predecessor Lady Eleanor, Margaret was known for her efficient management of the household and her connections to modern philanthropy.

Edward Talbot (42) - Future 9th Baron

The couple’s only son, who works in London but is being groomed to inherit the family estate and its responsibilities. He visits regularly and has a deep love for the village and its heritage.

The Chittlebury Bombing

On the night of April 24th, 1942, as Exeter Cathedral was under attack during the Baedeker Blitz, the village of Chittlebury experienced its own tragedy. A German bomber, en route to Exeter, jettisoned an incendiary bomb prematurely. The bomb landed on Main St, hitting a row of terraced railway cottages that housed line men and their families.

At the time, the men were away, working to repair damage to the nearby Chittlebury Tunnel, leaving their families behind. Fortunately, the families were sheltering in the stone crypt of St James Church, which was known to be sturdy and bomb-proof. The bomb set off a devastating fire that quickly spread through the terraced cottages, destroying houses 18 to 26 in a matter of hours. Despite the efforts of the villagers and the local fire brigade, the row of cottages was lost.

Aftermath

The fire was particularly devastating due to the close proximity of the houses, typical of terraced railway cottages. While no lives were lost, the destruction of the homes marked a significant blow to the community.

The cottages were never rebuilt. The land under them belonged to the railway company, and with the linemen relocated closer to Exeter, there was no longer a need for housing in Chittlebury. The empty plot remains a quiet reminder of the village’s wartime past, serving as an informal memorial where locals gather each year on Remembrance Day to honor those affected by the war.

The Memorial Garden

After the fire destroyed the row of terraced railway cottages on Main St, the railway company, in cooperation with the village, decided to turn the empty plot of land into a memorial garden. Since the land was no longer needed for housing, and with the proximity to the Village Green—which already had a WW1 memorial—it made sense to create a space that would honor both the railway workers and the community's shared sacrifices during both world wars.

The memorial garden was designed with a simple layout, featuring a few benches, flower beds, and a small stone plaque dedicated to the railway workers who had lived in the cottages. The garden serves as a peaceful place of reflection, where villagers come not only to remember the events of April 24th, 1942, but also to honor the broader history of the village during both world wars.

The garden, with its stone paths and carefully maintained rose bushes, also forms part of the Remembrance Day ceremonies held every year.

The WW1 memorial on the Village Green and the railway memorial garden across the street stand as twin reminders of the village’s resilience and the cost of conflict.

Railway Connections

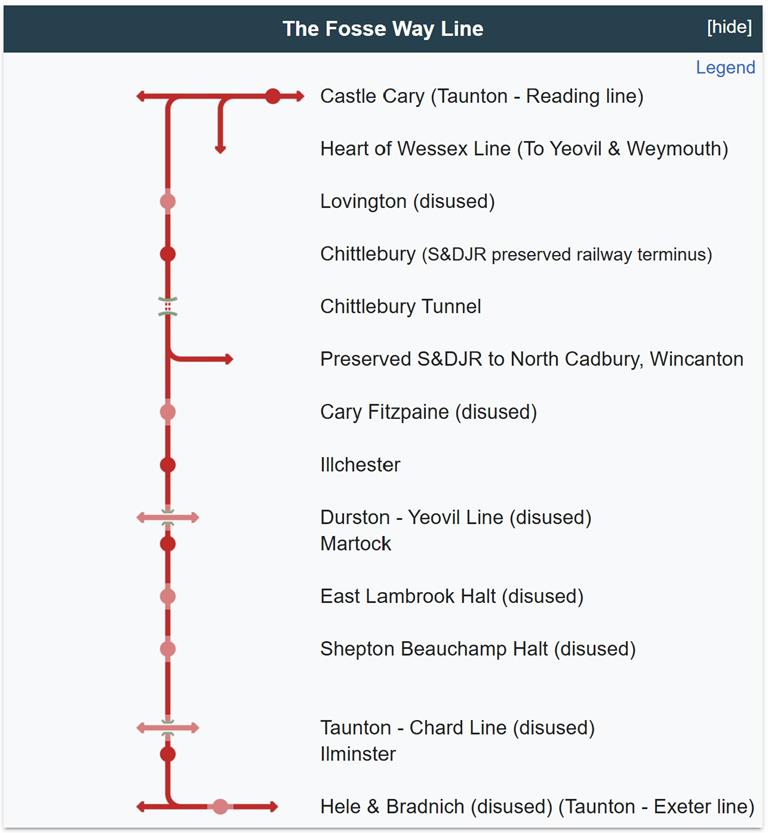

Chittlebury gained regional importance in the 19th century when it became a railway junction. The village was a key stop on the Great Western Railway (GWR)’s Fosse Way Line, which connected Exeter to Westbury via Hele, Illminster, Martock, Ilchester, Chittlebury and Castle Cary. The line provided a quicker alternative to the traditional Westbury - Taunton - Exeter route, bypassing Taunton and connecting Exeter with the rest of the GWR network.

The Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway (S&DJR) also planned to build a line west from Wincanton, aiming to reach Taunton and the north Somerset coast at Minehead. However, due to financial constraints, the line was never completed beyond Chittlebury. The S&DJR branch terminated at Chittlebury Station, where it met the GWR line, but did not cross it, preserving the rivalry between the two rail companies.

Despite the truncated line, the branch continued to serve the local economy, particularly the dairy industry and the nationally renowned Chittlebury Stud. The stud's proximity to Wincanton Racecourse made the village an important hub for transporting racehorses and dairy products to southern markets.

More Information

The Fosse Way Line

Around 1880 the Great Western Railway decided that it's "Great Way Round" was no longer fast enough for it's new trains from Paddington to the West Country

At the time, the board determined that Taunton was well served by trains on the existing Bristol-Exeter line, the priority for the new line was to take the quickest route from Westbury to Exeter, so the Fosse Way Line was born.

In later years Taunton's importance was recognized and the Castle Cary - Taunton line was also opened, over time this diminished the Fosse Way line and many of it's stations were closed during the Beeching cuts

Today the route continues to serve as an alternative to the Taunton route, particularly for freight and local traffic, though it also enjoys a daily commuter service to London called The Centurion in recognition of the line's name.

The Route

The line leaves the Westbury - Taunton line just west of Alford Halt, which in turn is just to the west of Castle Cary. It's first stop is the village of Lovington, just north of St Thomas of Canterbury's church. It then crosses the River Cary at 51.06824, -2.58912 before continuing south west to the village of Chittlebury, a halt is provided at Cary Fitzpaine somewhat to the south of the hamlet, before the line reaches the town of Illchester where a station was provided just to the north of the town at 51.00821, -2.67845 adjacent to the Fosse Way from which the line takes it's name.

From Illchester the line crosses the River Yeo at 51.00323, -2.69376 and passes through Ash just north of the Bell Inn, from there the line arrives in Martock where there is a station just to the south of Coat Road, adjacent to the station on the Durston - Yeovil branch line.

Leaving Martock the line crosses the River Parrett at 50.96811, -2.79525 with a halt at East Lambrook, just south of St James Church at 50.96417, -2.81032, another halt follows at Shepton Beauchamp on the southern side of Great Lane near the Duke of York public house.

From there the line passes just south of Dillington House before arriving in Illminster where there is a station on the northern side of Canal Way at 50.92886, -2.92697. Leaving Illminster the line passes to the north of Donyatt, then just to the south of Upottery Airfield and just south of the old part of Dunkeswell with a station at 50.85742, -3.22409 off of Manleys Lane. From there it runs alongside the Sidmouth Road from 50.81834, -3.39107 for about a mile before veering off at 50.81585, -3.40736 then curving round to join the mainline just north of Hele station at 50.81209, -3.42551

The entire route is just over 42 miles in length.

Services

Stopping Service: Runs 9 times a day with key stops at Chittlebury, Ilchester, Martock, Ilminster, and connections at Castle Cary and Exeter. certain services extend beyond Westbury to Swindon and beyond Exeter to Plymouth.

Express Services: Daily express service, THE CENTURION serving Westbury, Reading and London Paddington with return service in the evening.

Freight Services: Allocated time slots for freight during off-peak hours, ensuring smooth operations without disrupting the passenger flow.

Westbury to Exeter

Times leaving Westbury

| Time | Service Details |

|---|---|

| 05:30 | Early Morning Service (T2) |

| 07:30 | T3+T5 (Morning Commuter) 2 × 158 (Extends to Plymouth: Exeter 09:20 (dep 09:25), Newton Abbot 09:45, Totnes 10:05, Ivybridge 10:20, Plymouth 10:40) |

| 09:00 | T1 |

| 11:02 | T2+T4 From Swindon (dep 10:15 via Chippenham 10:30, Melksham 10:40, Trowbridge 10:49, Westbury 10:57) arr. Exeter 12:52 (T4 detached, onward to Plymouth dep 13:00, arr 14:15 using same stock as earlier T3) |

| 13:00 | T1 |

| 13:12 | Cross Country service from Sunderland, non-stop Westbury-Exeter (passes Chittlebury at 13:57) |

| 15:00 | T2 |

| 17:30 | T1+T4 (Evening Commuter) 2 × 158 (arr. 19:20, detaches additional 158 unit) |

| 19:30 | T3 (leaves T5 at Westbury) |

| 19:50 | THE CENTURION calls Chittlebury 20:30, Martock 20:45, Illminster 21:00, Exeter 21:20 |

| 21:30 | T1 (arrives Exeter 23:20 to depot) (Late Service) |

Exeter to Westbury

Times leaving Exeter

| Time | Service Details |

|---|---|

| 05:30 | THE CENTURION calls Illminster 05:50, Martock 06:05, Chittlebury 06:20, Westbury 07:00, Reading 07:50, London Paddington 08:25 |

| 06:00 | Early Morning Service (T1) |

| 07:30 | T2+T4 (Morning Commuter) 2 × 158 Train continues to Swindon, dep Westbury 09:25, Trowbridge 09:31, Melksham 09:41, Chippenham 09:51, Arr Swindon 10:10 |

| 09:00 | T2 |

| 11:00 | T1 |

| 13:00 | T2 (Connection from Plymouth dep 11:35 arr Exeter 12:50 uses same stock as earlier through service T3) |

| 15:00 | T1+T4 (picks up additional 158 unit) |

| 16:00 | Cross Country service to Sunderland, non-stop Exeter-Westbury (passes Chittlebury at 17:00) |

| 17:30 | T3+T5 (Evening Commuter arrives Westbury 19:20) 2 × 158 Starts from Plymouth 16:00 calls Ivybridge 16:18, Totnes 16:33, Newton Abbot 16:52, Exeter |

| 18:00 | T2 |

| 19:30 | T1 |

| 21:30 | T3 arrives Westbury 23:20 stabled overnight reattached to T5 (Late Service) |

S&DJR Preserved Line

Take a step back in time and experience the golden age of steam with the S&DJR Heritage Railway, an unforgettable journey along a beautifully preserved branch of the Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway. Stretching just over 8 miles, this heritage line offers a unique blend of nostalgia, scenic views, and local history. From the charming market town of Wincanton to the scenic halt at North Cadbury, and finally to its terminus at Chittlebury, this journey will transport you back to the heyday of British rail travel.

The Route

The heritage line begins at the northern end of Wincanton Station, where it diverges from the main S&DJR line. Wincanton, now home to the railway’s headquarters, boasts a newly installed but historic turntable in the former goods yard, where visitors can view several S&DJR steam locomotives on static display. Steam enthusiasts will love exploring the railway museum here, which offers insights into the Somerset & Dorset's rich history.

From Wincanton, the train chuffs its way through the Somerset countryside, traveling 4.5 miles to the halt at North Cadbury, a quaint stop that offers more than just a break in the journey. Here, passengers can hop aboard a vintage bus that provides transport to Cadbury Hill Fort, a site steeped in ancient history and one of the most iconic Iron Age hillforts in the region.

After leaving North Cadbury, the train continues for another four miles, winding through rolling hills and farmland. Before reaching its final destination, the line turns north to join the GWR Fosse Way Line, just south of Chittlebury Station. Thanks to the intervention of Lord Talbot, the former local MP, the S&DJR secured running rights over this half-mile stretch of GWR track, which includes the dramatic passage through Chittlebury Tunnel. The line culminates in a south-facing bay platform at Chittlebury Station, where visitors can explore the village and visit the ancient church of St James or simply enjoy the scenic setting.

Operations and Experiences

The heritage railway prides itself on offering a traditional steam train service between Wincanton and North Cadbury. Pulled by restored S&DJR steam engines, the train runs back and forth along this picturesque route, evoking memories of a bygone era when steam ruled the rails. The gentle chug of the locomotive, the hiss of the pistons, and the smell of coal-fired power will delight families, history lovers, and railway enthusiasts alike.

For those seeking a complete journey to Chittlebury, the railway operates a more modern yet vintage Diesel Multiple Unit (DMU) service. While Network Rail restrictions prevent steam trains from traveling over the Fosse Way Line, the DMU provides a seamless journey along the full length of the route, including the short stretch on GWR metals through Chittlebury Tunnel.

Wincanton Headquarters

The Wincanton Station complex serves as the hub of the heritage line’s operations. The newly restored turntable allows steam locomotives to be rotated and maintained, and the former goods yard houses a series of static displays showcasing the history of S&DJR steam engines. Visitors can explore the railway museum, where interactive exhibits and memorabilia tell the story of the Somerset & Dorset line's legacy.

Wincanton also features a railway café where visitors can relax and enjoy refreshments before or after their journey. Be sure to browse the gift shop for railway-themed souvenirs and mementos.

Special Events

The S&DJR Heritage Railway hosts a variety of events throughout the year, including:

- Steam Gala Weekends: Experience the full power and glory of multiple steam engines operating in tandem, with special services, guided tours, and photo opportunities.

- Victorian Heritage Days: Step back in time to the 19th century with costumed reenactors, period food, and vintage experiences for the whole family.

- Christmas Specials: Join Santa on board for a magical winter journey, complete with festive decorations, holiday treats, and a visit from Father Christmas himself.

Plan Your Visit

Whether you're a railway enthusiast, a family looking for a fun day out, or someone seeking a scenic escape into Somerset’s countryside, the S&DJR Heritage Railway offers something for everyone. Don't miss the opportunity to travel on one of Britain’s most charming heritage railways, where history comes alive with every journey.

For more information and to book your tickets, visit our website or contact the Wincanton Station ticket office directly.

Schedule

Weekday Service, operated year round Monday - Friday, except public holidays (DMU Only)

The S&DJR Heritage Railway offers a weekday DMU service, subsidized by Somerset Council, providing a convenient link between Wincanton and Chittlebury. This service is ideal for both local residents and visitors exploring the scenic Somerset countryside.

Trains run every 90 minutes from Wincanton to Chittlebury, with stops at North Cadbury.

First service departs Wincanton at 09:45.

Last return service from Chittlebury departs at 16:15.

Weekend & Holiday Service, operated from Saturday 24th May 2025 - Sunday 31st August (Steam and DMU)

On weekends, the S&DJR Heritage Railway offers a mix of steam-hauled services between Wincanton and North Cadbury, alongside limited DMU services running the full length of the line to Chittlebury. Steam trains depart Wincanton approximately every 30 minutes from 09:00 to 16:30, running to North Cadbury with opportunities to visit Cadbury Hill Fort. A vintage bus meets passengers at North Cadbury Halt to transport them to Cadbury Hill Fort (just over a mile away), providing a perfect family day out.

Weekend & Holiday DMU Service:

DMU trains run every 90 minutes from Wincanton to Chittlebury, stopping at North Cadbury.

First DMU departs Wincanton at 09:45; last return service from Chittlebury departs at 16:15

Fares

All fares are one-way single tickets, valid for one month from date of purchase, a 50% discount is available on a return ticket purchased at the same time, bewteen the same stations as the original ticket.

Wincanton to North Cadbury Adults: £10 Pensioners (60+): £8 Children (5-15): £5 Family (up to 2 Adults + 2 Children): £25

North Cadbury To Chittlebury Adults: £10 Pensioners (60+): £8 Children (5-15): £5 Family (up to 2 Adults + 2 Children): £25

Wincanton to Chittlebury Adults: £15 Pensioners (60+): £12 Children (5-15): £7 Family (up to 2 Adults + 2 Children): £35

Chittlebury to Wincanton Adults: £15 Pensioners (60+): £12 Children (5-15): £7 Family (up to 2 Adults + 2 Children): £35

Vintage Bus to Cadbury Hill Fort (from North Cadbury Halt) Adults: £3 Pensioners (60+): £2.50 Children (5-15): £2 Family: £8

Combined Tickets

Wincanton to North Cadbury + Bus: Adults: £12 Pensioners: £10 Children: £6 Family: £30

Wincanton to Chittlebury + Bus: Adults: £17 Pensioners: £14 Children: £8 Family: £40

Economy

Chittlebury’s economy has historically been centered on dairy farming, with the village acting as a collection point for high-quality dairy products. Milk, butter, and cheese were shipped by rail to Bournemouth, Exeter, and London, contributing to the village’s economic growth. The Chittlebury Dairy Co-op remains a major employer in the village today.

Additionally, the Chittlebury Stud, founded by Lord Talbot, earned national recognition for breeding and training racehorses. Many prominent racehorses have been trained at the stud, with regular shipments from Chittlebury to Wincanton Racecourse. The stud continues to draw owners and horses from across the country.

Notable Landmarks

Chittlebury Manor: The ancestral home of the Talbot family, the manor is a focal point of local history. Lord Talbot's ancestors are believed to have aided Charles II during his flight to France.

The Rectory: Built in the early 19th century, the Rectory was once home to a science-minded vicar during the Victorian era. Known for his experiments in natural sciences, the vicar’s work was locally renowned.

The Talbot Arms: This village pub, named after Lord Talbot, has been in operation for over two centuries. The pub is located next to the village green and serves locally brewed ales and traditional fare.

Village Store and Petrol Station: The Village Store serves as the local post office and grocery, while the adjoining petrol station operates a small Jaguar dealership, maintaining a connection to British automotive heritage.

Chittlebury Cricket Ground: Located near the Village Hall, the cricket ground hosts matches for the Chittlebury Cricket Club, established in 1878. The ground overlooks the scenic countryside, making it a popular spot for local gatherings and sporting events.

More Information

The Old Rectory – A Place of Invention and Intrigue

The Old Rectory, originally known as The Rectory, was built in the early 19th century, possibly as a rebuilding of an earlier structure, to serve as the residence for the vicar of St James Church in Chittlebury. The Rectory became known for its unusual and somewhat eccentric occupants, particularly during the Victorian era.

In the mid-19th century, Reverend Algernon Fitzwilliam, an eccentric and intellectually curious gentleman, became the vicar of St James. Fitzwilliam was a true Renaissance man of his time, combining his theological duties with a deep fascination for the natural sciences and mechanical inventions. Known in the village as the "mad inventor," Reverend Fitzwilliam spent his spare time conducting experiments in the rectory’s attic, turning it into a veritable workshop of oddities.

Fitzwilliam became locally famous for his work on early refrigeration systems and hydraulic pumps. One of his notable improvements was a system to improve the efficiency of water wheels, which were still commonly used in mills around Somerset at the time. His design for a self-regulating mill pump became a model for several local mill owners, improving water distribution during dry seasons. Although his inventions never reached commercial fame, they left a lasting legacy in Chittlebury’s industrial history.

Reverend Fitzwilliam was also obsessed with the idea of harnessing static electricity for practical use. Though his experiments with early electrical devices were largely failures, they provided much amusement for the villagers, who often saw strange lights flickering in the windows of the rectory late at night. It was said that Fitzwilliam’s obsession with science didn’t detract from his pastoral duties but instead added to his aura as a kindly, if slightly unhinged, country vicar.

Later History and Amalgamation

Following Reverend Fitzwilliam’s death, the rectory passed through a series of less distinguished incumbents, none of whom matched his intellectual vigor. By the 20th century, the role of the vicar in Chittlebury had diminished, and in the 1980s, the Diocese of Bath and Wells decided to amalgamate the parish with others nearby. St James Church was then served by a traveling vicar, and The Rectory was no longer needed as the vicar’s residence.

The house was sold and renamed The Old Rectory, becoming a private residence. The building, with its high ceilings, large windows, and sprawling gardens, still retains much of its original Victorian charm.

In recent years, The Old Rectory has been home to Beatrice "Bea" Harrington, a retired detective chief inspector from London.

Bea Harrington

After a successful career in law enforcement, Harrington relocated to the peaceful countryside of Chittlebury, seeking solace from the bustle of city life. However, retirement didn’t mean rest for Bea—she soon turned her hand to writing, and under the pen name Henrietta Vale, she has become a nationally acclaimed murder mystery novelist.

Her novels, featuring the sharp-witted detective Vera Hazelton, have garnered a loyal readership across the UK. With a mix of traditional British whodunits and psychological intrigue, her books often draw inspiration from her experiences in law enforcement. Locals have speculated that some of her stories might even be based on real-life cases she worked on, though Bea never confirms or denies the rumors.

Now a fixture of the local literary scene, Bea Harrington occasionally hosts book signings and readings at The Talbot Arms, delighting both villagers and visitors with her dry wit and storytelling prowess. Her home at The Old Rectory serves as both a peaceful retreat and a creative sanctuary where she continues to write, surrounded by the history of the house and its former inhabitants.

Henrietta Vale's Novels

Beatrice Harrington, writing as Henrietta Vale, has gained national attention for her series of detective novels featuring Vera Hazelton, a retired detective inspector who finds herself embroiled in mysteries in the English countryside. Her most famous works include:

- The Murder at Misty Moor

- A Death at the Vicarage

- The Silent Witness

- The Chittlebury Chronicles

The Talbot Arms

The Talbot Arms at 17 Main Street in Chittlebury was historically a tied house owned by the Devenish Brewery, based in Yeovil. Devenish Brewery had been a significant player in the West Country's brewing industry, known for its range of ales and its network of tied pubs across Somerset and the surrounding regions.

In 1993, Devenish was taken over by Greenall Whitley (now known as The De Vere Group). Following the acquisition, Greenall Whitley began to shift its focus towards the hospitality sector, leading to the closure of Devenish's brewing operations. Many of the tied pubs formerly owned by Devenish were sold off as Greenall Whitley exited the brewing business.

One such pub was The Talbot Arms, which was sold in the mid-1990s. It was purchased by it's landlord and became an owner-occupied establishment. Today, The Talbot Arms is a free house known for serving a selection of ales from independent Somerset microbreweries, continuing to honor its long-standing tradition of offering quality local beers.

- Landlord: Tommy Harford (52) – The long-serving landlord of the Talbot Arms. A former soldier, he's well-liked by the locals and has been running the pub for over 20 years. He lives above the pub with his family.

- Susan Harford (49) – Tommy's wife, who helps manage the day-to-day running of the pub and oversees the kitchen. Known for her famous homemade pies.

- Daniel Harford (23) – Their son, who works behind the bar in the evenings and is training to take over the family business.

- Black Sam: The ghost of Black Sam, a smuggler from the 17th century, is rumored to haunt the pub, particularly the cellar.

Saxon Period (Pre-1066)

Manor Holdings: As the Lord of the Manor, Beornwulf and his predecessors would have controlled several hundred acres of farmland, likely supporting a small village. During the Saxon period, landholdings were primarily for subsistence agriculture—grazing for livestock, small crop fields, and woodland for timber and hunting. The land would have been organized into open fields managed by the village community under the lord’s oversight.

Typical Acreage: Between 500 and 1000 acres, including both arable land and woodland.

Manor House: Likely a Saxon fortified homestead, consisting of wooden structures with thatched roofs. It would have been defensible, with wooden palisades or earthworks for protection from Viking raids and other threats.

Norman & Early English Period (1066–1400)

Manor Holdings: After the Norman Conquest, Chittlebury Manor became part of the Duchy of Cornwall, with the Talbot family serving as the feudal lords. Under Norman rule, the manor system formalized the division of land between the lord, tenant farmers, and serfs. The Talbots would have controlled additional tenant land beyond their original holdings.

Typical Acreage: Expanded to between 1000 and 2000 acres, including tenant farms, pasture, and hunting land. By now, the family likely oversaw villagers, farmers, and woodlands, providing resources like timber for the local area.

Manor House: The Norman Talbots likely built a small stone castle, replacing the wooden fort. This castle would have been relatively modest compared to major fortifications but strong enough to defend against local threats. It might have featured a keep, a stone wall, and a moat. The castle would dominate the village and reinforce the Talbots' feudal authority.

Late Medieval and Tudor Period (1400–1600)

Manor Holdings: By the 15th century, the family had expanded their holdings further as Chittlebury became a thriving estate under the Duchy. They would have benefited from the prosperity of the Hundred Years’ War and the shift to pastoral farming (particularly sheep). During this time, tenant farms likely expanded, and the family invested in local industry (possibly wool or milling).

Typical Acreage: Now approaching 3000 acres, including tenant farms, orchards, grazing lands, and possibly mills for processing wool.

Manor House: The original Norman castle likely became obsolete, and the Talbots abandoned it in favor of a Tudor-style residence. This new house would have been built of brick or stone, featuring gabled roofs, large tall chimneys, and mullioned windows. The Tudor residence would have been a status symbol, reflecting the Talbots' growing wealth and influence, and likely included a Great Hall for feasts and social functions.

Georgian and Victorian Periods (1700–1900)

Manor Holdings: By the Georgian era, the Talbot family had become more involved in local politics and national trade. With Andrew Talbot working overseas and Sir Edward expanding into industrial investments (especially railways), the family began to consolidate their wealth. By the Victorian period, tenant farming had declined, and large portions of the estate were now used for commercial farming or leased to local tenants for sheep farming and agriculture.

Typical Acreage: During the Victorian era, the estate could have grown to 5000 acres or more, largely due to Edward Talbot’s industrial wealth, enabling land purchases.

Manor House (Palladian Rebuild): By the mid-19th century, Sir Edward Talbot, 4th Baron, likely decided that the old Tudor house was no longer fashionable and ordered it demolished in favor of a Palladian mansion. This new house would have been symmetrical, with columns or pilasters on the front façade, and large windows to let in light. It would have been a reflection of Sir Edward’s wealth, status, and modernity, showcasing his involvement in railways and mining. This house features expansive gardens, perhaps modeled after the English landscape garden movement, with wide lawns, groves of trees, and formal terraces.

WW2 – A Secret Hub for D-Day Reconnaissance

During World War II, The Manor in Chittlebury was quietly requisitioned by the British government and became an essential, though hidden, cog in the machine of D-Day planning. It was assigned to a team led by Colonel Henry "Hank" Davidson, an officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, specializing in stealth reconnaissance and covert operations. His task was critical: to oversee the preparation of reconnaissance missions across the southwestern coast of England, particularly in gathering crucial intelligence on beaches and terrain that would play a pivotal role in the Normandy Invasion.

Operations and Coordination

With Weymouth and Portland serving as key embarkation points for U.S. troops, and RNAS Yeovilton acting as an important hub for naval aviation, The Manor was strategically located. Colonel Davidson's team directed aerial reconnaissance missions using stealth aircraft designed to capture detailed images of Normandy's beaches and inland areas, while also overseeing covert operations that monitored German troop movements across the English Channel.

The Manor's secluded location provided security, while its proximity to key airfields such as Yeovilton and Exeter allowed for quick access to planes, equipment, and command personnel. Intelligence gathered was vital in selecting landing points for the invasion, assessing coastal defenses, and planning paratrooper drops.

Key Missions and Personnel

Colonel Davidson’s team was small but highly skilled, including reconnaissance pilots, intelligence officers, and cartographers, who worked tirelessly in the weeks and months leading up to the invasion. Their work was often carried out under the cover of darkness, with maps and aerial photographs being analyzed late into the night. The team coordinated closely with British military and RAF units in the region to ensure that all intelligence was shared efficiently with Allied command.

Lady Celia Talbot was known to have been a quiet but important local supporter of the operation, allowing her home to be transformed into a secret military hub. The work carried out within the manor’s walls was so secretive that even the village residents were largely unaware of the role it played in the larger war effort.

Aftermath and Legacy

Following the success of Operation Overlord and the D-Day landings, The Manor was quietly returned to the Talbot family. However, the significance of its role in reconnaissance and planning operations was kept secret for many years, and only later did it become known that Chittlebury had played such a vital part in one of the most important operations of WWII. Today, a small plaque in the memorial garden across from the Village Green commemorates the efforts of those who worked there, though many of the details remain lost to time.

Annual Events

Chittlebury holds its annual Fête on the Green, a village festival featuring local food, music, and traditional games. The event is one of the highlights of the year, drawing attendees from neighboring villages and towns.